My office job used to pay 258,000 yen/month after income tax, pension, city tax and health insurance. That sum of money you take home is called ‘tedori’ in Japanese. So, my tedori used to be 258,000. Life wasn’t all sapphires and private jets but it wasn’t an awful wage.

Later this week I have my first payday for a full month’s work as a cleaner. Cleaning’s making me just over 1,200 yen/hour and I do it roughly full time. If you multiply this rate by the hours I do, you get about 180,000 yen. After deductions for tax, pension and whatnot, the tedori is going to be significantly less.

So, I’m apprehensive. And I will need to tighten my belt.

I don’t have ostentatious habits at present; I don’t buy music or clothes, eat out too often, go to Starbucks every day or collect gadgets. I own two or three pairs of shorts, a couple of pairs of sweatpants, two pairs of underwear, a couple of jackets, some t-shirts, about three pairs of socks, one pair of outside shoes, and some raggedly old formal clothes. I may have a half dozen decent shirts that I wear during live readings, and a pair of slacks somewhere. I possess a total of two plates.

But I buy second-hand DVDs (at 550 yen, they seem a better deal than online rental), and ride about on trains a fair bit. Plus, I buy sweets: ice cream, chocolate bread, and Costco muffins. These are things I may cut down on, depending on what this week’s pay slip says.

I don’t mind consuming less, though, because I like a simple life. I don’t want objects and expensive habits. I want a ramshackle country house to repair. I can sacrifice a lot for inner peace, which to me means my own living space, enough cash to eat, and an occupation that keeps me away from office buildings.

I’ve had money in the past… and, also, I’ve been hard up. I’ve never been poor in the sense of struggling to eat, of experiencing real fear over what might become of me. But I have been hard up… and very happy at the same time. No video game or pricey shirt has ever granted me the serenity I get from watching the ocean, just as no back pat from an office boss is as good as a cool breeze on my face.

That’s why I’ll continue to clean, to do manual labour, and to work outside. I’ll make my finances suffice one way or another, but I won’t be returning to the land of Venetian blinds and photocopiers. The income I have lost by refusing to don a suit and tie just isn’t worth going back for.

Yesterday, I was on my way out and saw two coworkers talking. It was the middle of the day and they had on pristine office threads, clean shoes, and belts. They were clean-shaven with nice haircuts. One was clearly senior, probably the other guy’s section chief or something. They were discussing an internal phone call from their company CEO, the message that call conveyed, and an obligation they had to one of their customers.

But, more than the content of their conversation, I was focused on the dynamic between them. They knew each other well, that much was clear, and yet there was a tenseness, a hierarchical relationship that bolted them both together and apart. When the senior man spoke, he communicated, of course, the information he wanted to, but there was a layer of image-crafting there, that constant performance of the socially recognised role of boss, the eagerness to impress upon his junior that he cared about the correct things in the right, responsible way.

The junior man, for his part, enacted the image of the keen and thoughtful supplicant, an engaged and conscientious functionary that his manager could rely on. Possibly, there was little self-awareness of this in either of them because their image-crafting patterns of speech, their pauses, their gestures, and the carefully modulated graveness of their tones long ago became second nature.

One reason I failed to fit into corporate culture was how hard it all made me cringe. I simply couldn’t help but say I didn’t care, mouth off, disagree, make odd jokes. The longer I did office work, the more visible and extreme my innate recalcitrance got.

None of this is to say, of course, that we don’t perform work-based roles at the dispatch office of a cleaning company, roles based on broader, standard social practice. But they are lighter, less onerous, and seemingly more flexible. The perceived status gap between workers and managers (who generally started their employment at the company as cleaners themselves) feels narrower, and jokes are more acceptable.

The higher staff turnover - and the fact that the company is short-staffed - seems to have occasioned a lighter touch, and fewer and gentler scoldings. Because the work itself is simpler, discussions of methodology are brief, freeing up more time for friendly banter. Perhaps, also, the fact that they don’t pay us too much makes them feel they ought to be nice, in contrast to some office overlords who act like they have a bundle of javelins up in their back passage.

There’s no fucking way I’m applying for any more jobs in some shithole open plan office dump with no privacy, even if it means not having disposable income. That’s how strongly I feel about it. I’m thinking I’ll blow the rest of my savings on an abandoned house so I don’t have to pay rent any more, eat cheaply, and watch the same few DVDs if I have to. But I won’t go back in any crappy cage from 9 to 6 making spreadsheets unless I’m marched there by men with machine guns.

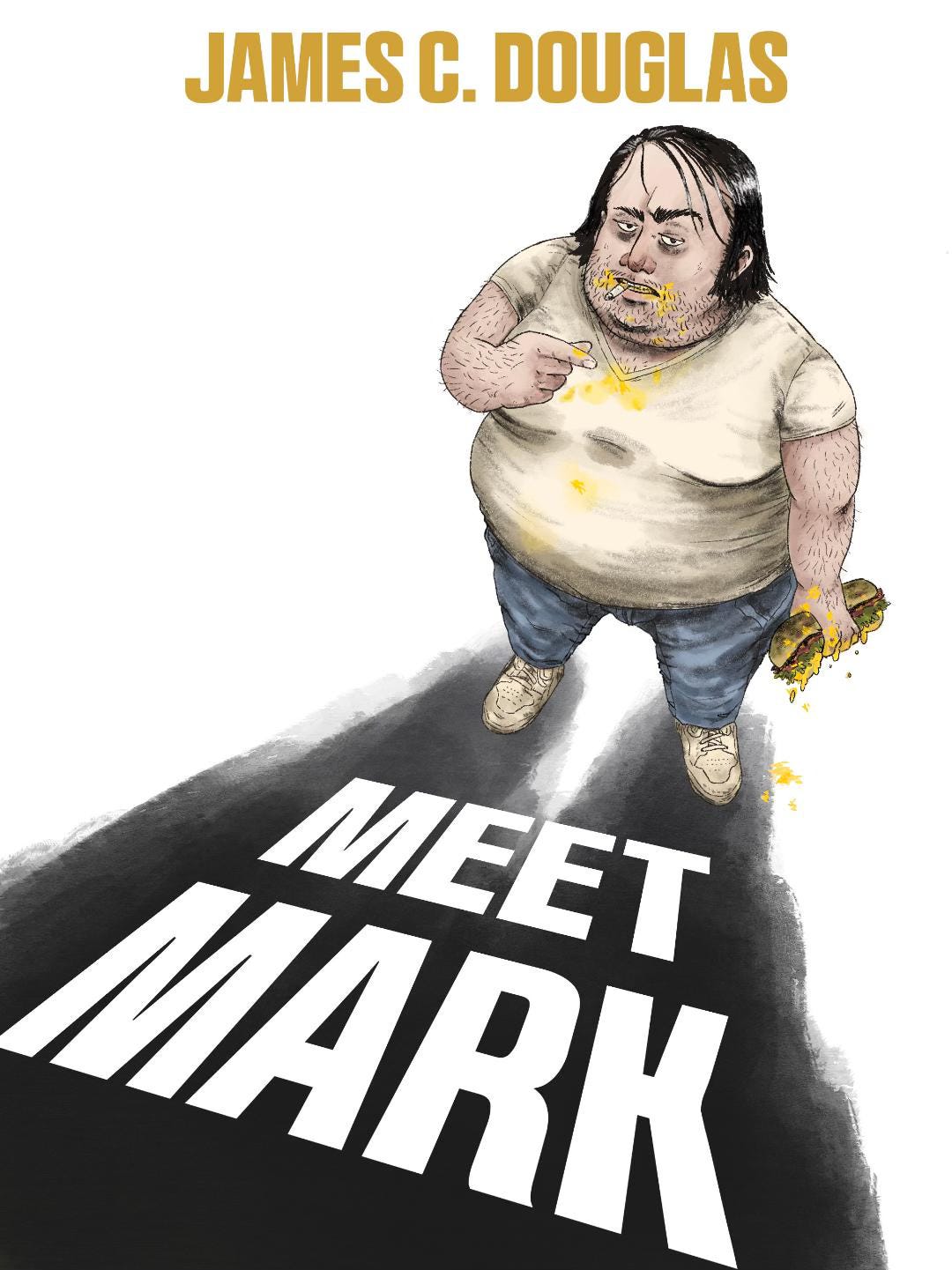

PS. Here is a funny book I wrote.

Part 27 of this blog is here.

And the previous part of this blog series is here.